Engine, gearbox and exhaust

When considering any ancient Brit parallel twin it is essential to remember that Triumph were first. And indeed last. All the other competing companies’ designers tried – and often succeeded – to improve on the Triumph original. The Norton twin – as seen here – is like that.

Norton’s boss designer, a fine fellow name of Bert, wanted to improve on the Triumph twin, while producing comparable performance at a comparable price. So, rather than using Triumph’s vintage external tubes to contain the pushrods which prod the overhead valves, he had tunnels cast into the cylinder block.

That made the block more expensive, so he saved money by employing just the one camshaft, as opposed to the Triumph’s two. That shaft sits at the front of the engine, spinning in a trough of oil, and is rarely a problem… except when the occasional batch of soft steel was used, but that’s not a design flaw.

The next step was to cure the leaky top end, which was accomplished by casting the head and rockerboxes as one unit, which stops leaks between the top end joints … because there are no top end joints. Again, this makes for an expensive casting, and costs were saved elsewhere by using chains to drive both the single camshaft and the magneto, rather than the expensive precision gears employed by Triumph. So, we have a neat engine design with fresh thinking applied, gained from several years of experience watching how Triumphs performed in the real world.

The first Norton twin engine displaced 497cc from internal dimensions of 66 x 72.6mm. The first of the several stretches came for 1956, when the engine was bored and stroked to 68 x 82mm, providing a rousing 596cc. 1960 introduced a stretched stroke, hefting the twin to 68 x 89mm and 646cc – the first of many Norton 650 twins. By 1962 the inevitable Americans were demanding more cubes and Norton obliged with the first 750 – boring their twin to 73 x 89mm and 745cc. Hurrah.

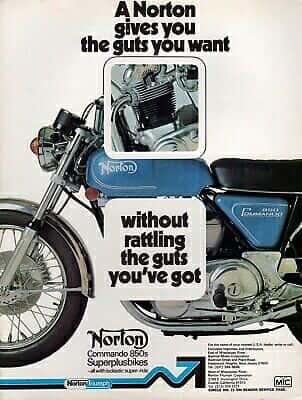

That engine was used in several models and is in fact a completely cracking device, and when the freshly revived Norton concern was looking for a great new superbike engine to combat Honda and the like… their best efforts were no more powerful. Which is why the first of the Commando line used this engine when 1967 produced Sergeant Pepper and the Norton Commando. Hurrah for both. Steady development followed, and eventually in 1973 Norton performed the final overbore, taking their venerable engine out to 77 x 89mm and 829cc.

A few fairly serious problems with tuned 750s encouraged their new 850 to aim for more torque than power, so the last engines hiked the power from 60bhp at 6500rpm to 58bhp at 5900rpm, which produced the stump-puller we’ve already mentioned. That sounds a little sarcastic, but it’s not. The last of the 850 twins – seen here – is a gloriously relaxed and entirely enjoyable powerplant. It’s even quiet, so quiet that most owners ditched the quiet annular discharge silencers for the earlier ‘pea-shooter’ reversed cone megaphones, as also seen here. A couple more decibels and a couple more ponies too. It’s difficult to explain how different an engine this is to its Brit competitors. It’s never frantic, never in a rush, never bursting to go faster.

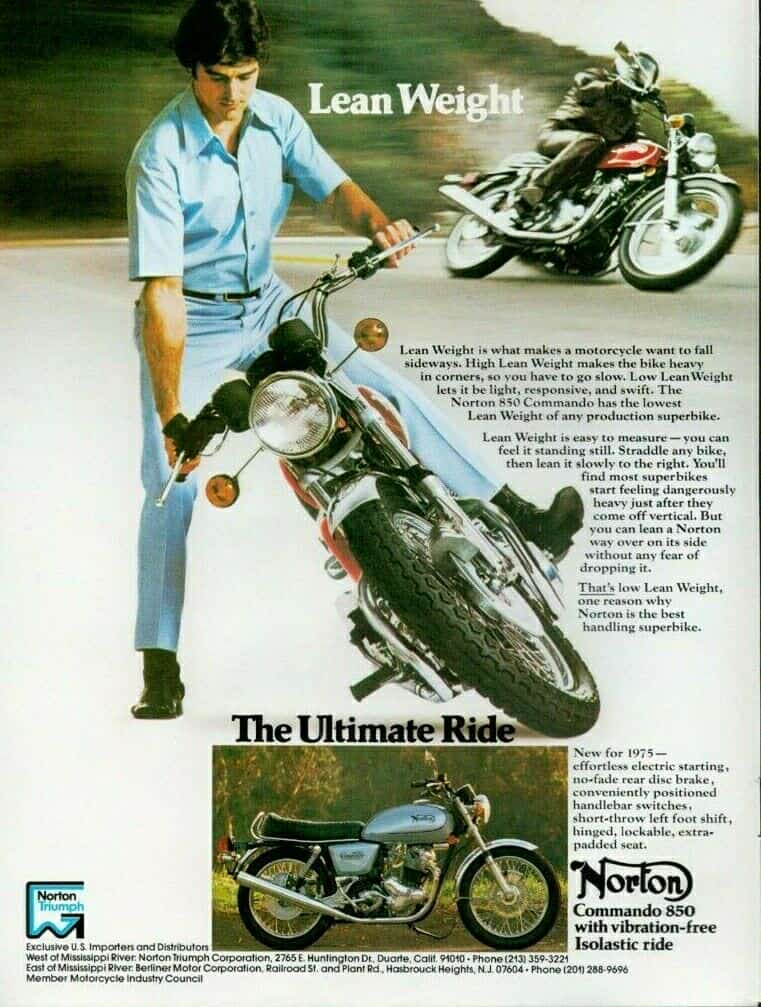

But it will run at 4000rpm – 75mph or so – all day, every day. And it’s relaxed and reliable doing this. Not all Brit twins are like this. The gearbox is another reason for the unique charm of the Commando. Introduced in 1956 and known variously as the AMC gearbox or the Norton gearbox, depending on who’s talking, it stuck steadfastly to its original four speeds, although their spacing changed over years, as you’d hope. The shift is clean and precise, fairly quick for a box of its type, and for the final Mk3 model the shift was … ah … shifted from the conventional Brit right foot to the left, as demanded by those mysterious Americans.

This change in turn dictated a new primary chaincase, with a tensioner for the chain itself and room for all the electric start gubbins. Did we forget to mention that the final Mk3 Commandos boast that ultra-modern device, the self-starter? Well, it does. And although their reputation was terrible – a joke even – for many years, the fix has been in for many more years now

. You know: turn key, apply thumb to switch and click-brumm. It is always a surprise when one works… It’s too easy to make jokes about the old-fashioned 4-speeder, but that’s actually missing the point in this case. The engine’s wide power delivery and flexibility allow the gearbox to have four very long ratios.

None of this top gear as an overdrive nonsense, either. What you get is a rare opportunity explore a whole small world of an exceptional riding style that’s largely missing in these latter days of 6+ speeders. Exhausts were several. This, the last of the big bangers had a nice simple system, just two headers joined by a balance pipe and with very quiet silencers. Most owners replace this with two headers without the balance and that set of megaphones. So should you.