Blog

Tribute Run to Father Graham Hullett and the roots of British two-wheel Revivalism

6/6/13

Tribute Run to Father Graham Hullett and the roots of British two-wheel Revivalism

‘They paved paradise and put up a parking lot’

Words by David Lancaster

Pictures © David Lancaster & others

Saturday, May 4th: Paddington, west London. BSAs, Triumphs, Nortons and Norvins appear. Rain subsides and riders gather.

From the mid-1800s ‘till the Second World War this area around the arm of the Grand Union Canal saw a bustling traffic of narrow barges unload their wares into the metropolis – and then turn to make their journey back to England’s industrial heartlands in the Midlands.

The trade declined after the War. As did Paddington, at least on the surface. But boat dwellers took up residence on the neglected canal, including me in the 1990s. And yards from the canal, in the 1960s, the hall attached to St Mary’s Church was home to the 59 Club .

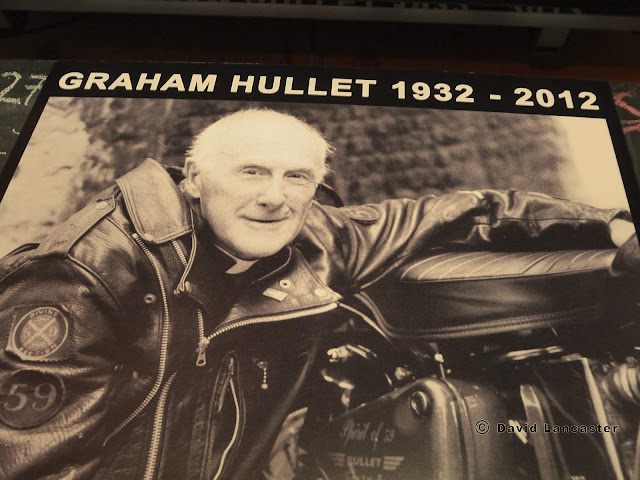

The 200-odd bikes and riders were gathering on the site of the hall to pay tribute to Father Graham Hullett, who passed away last year; the last man of the cloth to shepherd the young motorcyclists who congregated at the Club first in Paddington, and later in Hackney. A ‘burn up’ run would follow, from the old Club HQ, down to Chelsea Bridge and Battersea pub The Pavilion.

Organiser was Lenny Paterson, the man who kicked off the original Rockers’ Reunion Runs in the early1980s and veteran of the 59 Club in its heyday. ‘It was a magic time,’ he recalls. ‘There were fewer speed cameras, and a real sense of freedom in terms of mobility and sexual freedom.’

Under the guidance of the motorcycling clergy of first Father Bill Shergold, and then Graham Hullett, its members married motorbikes with rock and roll in a very British way: ragged, yet elegant. As many of the pioneers remain. And Hullett in particular was a real motorcyclist as well as a man of faith. He rode his BSA far and wide – to the Elephant rally several times and to the TT every year. His also amassed an impressive photographic archive of the time.

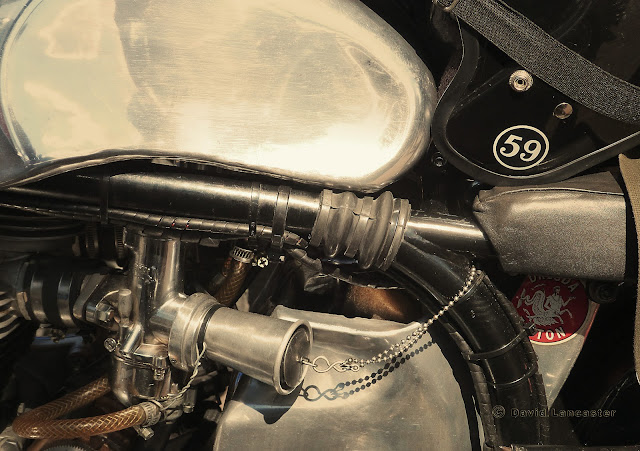

‘Graham was one of the boys, but there was an air of respect about him,’ Paterson recalls. ‘It was a gift. And one he wasn’t aware of. If you were out of order, he’d tell you.’ Paterson has more reasons than most to be thankful for this. With brushes with the Police piling up, his life reached a crossroads with a fight in the Club in the late 60s. Graham Hullett intervened and then talked the victim’s family out of pressing charges. ‘That was a turning point in my life,’ Len says. Payback came years later, when he organized the fund-raising to buy Father Hullett the Enfield 500 he spent his later years happily riding.

The Club under Father Hullett’s leadership kept the flame alive other ways, too. Laszlo Benedek’s groundbreaking film The Wild One had been banned by the British Board of Film Censors since its US release in 1953. The authorities were fearful the film might unleash riots in cinemas. A fanciful notion now, but the 1955 Blackboard Jungle did just that, with south London Teds trading punches and furniture at several screenings, soon copied across the land.

In 1968 the 59 Club’s Paddington HQ, as private members’ club, was able to screen The Wild One for the first time in the UK. And it was the film’s screening, along with home-brewed movies such Psychomania and bike-sploitation pulp fiction books like Stuart Hall’s Wheels of Death, which heralded a further gear-shift in street biking style – from clip-ons, rear-sets and black leathers, to the bobbed/chopped styling cues and cut-offs re-emerging today.

Brando’s stock Triumph, and rocker-style plotted one course – whilst the bobbed Harleys and Indians of Lee Marvin’s crew plotted another. According to George Harrison, it was this gang, ‘The Beetles’, which inspired the name of the Liverpool beat combo. As filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard said: ‘It’s not where you take things from – it’s where you take them to.’

Lenny’s Rockers’ Runs of the 1980s played just as important a role in laying the ground for today’s two-wheel canvass – uniting fans of British and Italian sports bikes, café racers and home-moddied specials, pretty much for the first time.

‘It was the same spirit as at 59 Club at its peak,’ he says. The backdrop of violence of London in the 70s – which crossed race, motorcycling, music and fashion more than many realise – had eased too, by then. ‘The back patch thing had simmered right down. Normal lads were out again.’ These were joined by the embryonic Mean Fuckers MC along with workers, friends and customers from Lloyd Johnson’s store La Rocka! and 1000s of others – old and new from London’s alternative motorcycling scene running down to Brighton from Chelsea Bridge.

This legacy of both the 59 Club and the Runs Len put together is more evident than ever these days – in everything from naked Triumphs and Nortons, to short films, independent builders, web sites and clothing. The road furniture and plodding four-door saloons from the 60s and 80s have dated dramatically, yet the appeal of the bikes and riders’ style is as stark today as ever, maybe even more so.

Surprisingly, much of the British bike mainstream failed, at first, to recognize this niche emerging before its eyes. An exec from the then-fresh Triumph firm told me in 1990 that, no, the Bonneville name would not be any use to them: ‘A few mates dressed in leather jackets do NOT constitute a market,’ he confidently commented on some 7,000 turning out for a Reunion Run. And an editor on Motor Cycle News asked Len just what his Rockers’ Runs ‘really had to do with motorcycling?’ As Len observes: ‘Even in the 80s, we [Rockers] were still being looked down on a bit.’

How times change. Brands, from Triumph to Levi’s, have realised the wealth contained in their own back catalogues, looking back for inspiration in order to move forward.

So the plot of land – now a car park – on which Club members gave three cheers in memory of Father Hullett has a key place in British two-wheeled culture. From ground-breaking film screenings, to the genesis of both the style and personnel of the original Rockers’ Reunion runs 20 years later, Paddington may have changed – but the style, lust for the road and the independent spirit of men such as Graham Hullett lives on.

Quite a legacy for a church hall.